Communicating and Collaborating Across Disciplines

published Nov 27, 2017 9:56amThose of us who are working on ways to attract students to the study of STEM fields must design a curriculum that prepares our students to understand and manage complex problems where scientific knowledge interacts with other ways of looking at the world. This means finding ways to work across disciplinary boundaries so that these problems can be studied in their broader social, political and environmental context. Boyd (2016, p. B4) argues that "if we really want to matter, we need to think critically about the questions we ask---and the questions we don't ask---and what influences that distinction." The questions we ask have powerful effects on how we design the curriculum, what we expect of ourselves and our students and how we work together with colleagues in our own department as well as other fields to prepare our graduates to live and work in a changing and uncertain world.

If STEM is to be relevant and have the best chance to serve the needs of society, we NEED to work with other disciplines. One way to open up an interdisciplinary conversation is to connect your goals for STEM education to existing cross-cutting themes that draw upon the insights of other fields as well. For example, consider developing a program that explores the local region in a variety of ways including a study of the regional ecosystem, the cultural heritage of the region, the literature and the arts that draw inspiration from the region and so on. These ventures can create synergies across departmental lines and draw on the distinctive strengths of many fields.

Another option is to connect your curriculum to larger challenges facing your community. One challenge facing every community is how to create greater resilience in the face of natural disasters including earthquakes or extreme weather events. The UrbanRISKLab at Massachusetts Institute of Technology has developed an approach to disaster management called PREPHubs. PREPHubs are a new kind of infrastructure designed to increase disaster resilience. Portland State University along with Portland Gas and Electric and the City of Portland are working together to bring this model to Portland, Oregon, where a magnitude-8 earthquake may occur sometime in the next 50 years (Meyer 2016, Schultz 2015). Engineers can design the overall module including power generation and communication capacity but this approach is incomplete without thoughtful attention to how people would use this network. In short, engineers can solve the technical problems but they will need to work with others to address the "human engineering" that will make the solutions workable in this particular region and its people.

Yet another way to manage this task is to pick a topic that concerns everyone, regardless of field, and work with colleagues across the institution to ensure that the institution itself models effective ways to address that problem---whether it is equity and inclusion or civic engagement or a complex problem like climate change. We all know that gaining support for addressing climate change depends upon much more than presenting the scientific evidence of global warming. We need to understand why facts alone cannot convince the skeptics and present the issue in different ways such as the economic advantages of alternative fuels or green buildings and green urban design. Our graduates must be able to weave their scientific knowledge into broader arguments and solutions.

To ask questions that matter, not only to us and our students but also to our colleagues in other fields and to the public, we need to understand how people in other disciplines think. Disciplines differ in the extent to which they use well-articulated frameworks or theoretical models or paradigms to guide their approach to problem-solving, the methodologies that members of that discipline are likely to use to study those questions and the standards that they apply to gauge the validity of the findings they obtain. Every discipline has its own vocabulary as well as its own unspoken assumptions about what questions and knowledge are legitimate.

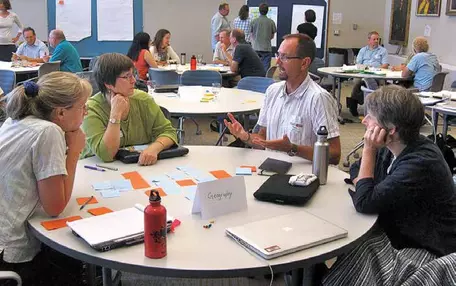

Working across disciplines requires diplomacy, mutual respect, some agreed-upon common ground and a willingness to learn, along with an understanding of the politics of a campus community and some experience in navigating the political environment. In a recent study, Peffer and Renken (2016) explored the ways that STEM investigators who follow a discipline-based approach to exploring how students learn science often fail to understand or appreciate the ways that social scientists pursue the same goal. ASCN participants have raised some very good questions about how to work with colleagues from other fields and sometimes, even colleagues in another subfield of their own discipline. Getting to know another field well enough to work within a new context is similar to traveling abroad. When communicating with someone who does not speak your language, it doesn't help to say the same thing more loudly or to become impatient because others simply don't understand what you are trying to say. What is needed is patience, a strong sense of curiosity and a good guide book.

Here are some steps to consider as you set out to work with colleagues across your campus (adapted from Peffer and Renken 2016).- Take time first to talk with your colleagues in various STEM fields about what the practice of science means to them.

- When you are talking with people from fields other than STEM, spend some time learning about how their disciplines are similar to or significantly different from your own. Ask about what kinds of questions are currently being explored in their fields and where the challenges and controversies are in their disciplines. Chances are that many of your faculty colleagues, like you, are trying to figure out how to prepare their own graduates to contribute to the study and management of the large-scale and wicked problems that people around the world must resolve. As in any negotiation, start by looking for common ground. What are their concerns about the curriculum, about what their students are learning, about the condition or status of their discipline, about the world in general?

- Take the time to develop a clear sense of how the various disciplines can contribute to the larger goal of preparing students for life and work in an uncertain world. How can you work together to reduce achievement gaps or to improve graduation rates or whatever other overarching goal your institution has embraced that will require collaboration and a sense of shared responsibility for the outcome.

- When you are planning interdisciplinary work, create well-defined roles for the participants that draw upon their skill sets and different perspectives. Make sure that what you propose to do promises to be mutually beneficial for the people who take part in the project.

- Take time to decide what evidence you will collect to guide your efforts and to measure your progress toward your goals. What you want to know may be different from what your colleagues in other departments care about.

Suggested Citation

Ramaley, J. A. (2017, November 27). Communicating and Collaborating Across Disciplines. Retrieved from https://ascnhighered.org/ASCN/posts/192300.htmlReferences

Academic Disciplines-Disciplines and the Structure of Higher Education. Retrieved from http://education.stateuniversity.com/pages/1723/Academic-Disciplines.html on November 9, 2017Boyd, Danah (2016) Why Social Science Risks Irrelevance. The Chronicle Review August 5, 2016 pages B4-B6

Meyer, Robinson (2016) A Major Earthquake in the Pacific Northwest Looks Even Likelier. The Atlantic. Retrieved on November 23, 2017 from https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2016/08/a-major-earthquake-in-the-pacific-northwest-just-got-more-likely/495407/

Peffer, Melanie and Maggie Renken (2016) Practical Strategies for Collaboration across Discipline-Based Education Research and the Learning Sciences. Life Sciences Education 15(4) Retrieved from https://www.scribd.com/document/334759177/CBE-Life-Sci-Educ-2016-Peffer-pdf on November 9, 2017

Schultz, Kathryn (2015) The Really Big One. The New Yorker. Retrieved from https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/07/20/the-really-big-one on November 23, 2017.

Comment? Start the discussion about Communicating and Collaborating Across Disciplines